ACTION GRAPHISM

by Alexandra Samoilă

Those books that I will never read occupy a special place in my library. I’ve hidden them among the readable ones so they can feel at home but I can sense they don’t give a damn about feeling at home, on the contrary, they seem quite proud of their outcast status. I have for them the same scared politeness you experience as a child when you have to play the role of the well-behaved in front of a broad-shouldered friend of your parents. My respect for their incomprehensible content keeps me at distance.

One of them, On grammatology has a green circle drawn on the cover around which are written in a numismatic fashion the name and the surname of the author, in small letters! The cover is a matte white and I remember buying it when I proudly quit my first job. I was just taking a sip from the soon to be emptied martini glass of financial independence when I threw myself head onwards into buying books with fancy covers. And everytime I quit a job I have a short period in which I buy books I would otherwise not even look at.

The second one, Les pensées” of Lacan, was a more accidental encounter. I found it outside, in front of a booskshop in Lyon called Librairie Esperluette, among the other books. In French, the word “esperluette” which makes me think of “alouette”, translates in human words the typographical sign “&”.

Inside the bookshop, where the spines of her siblings were shining like freshly painted Corvettes, I heard the librarian whisper “une future psychanalyste” and I blushed because I know I’m as far from ever being a psychanalyst as I am from being a Formula One driver. After I left the library, I started walking differently, feeling a little of a psychanalyst, looking at people through the lenses of this newly acquired profession, asking myself what’s hiding in the graphism of their walk.

I buy difficult books in moments when I feel good about myself, when I have a boost of confidence. Otherwise, how could unreadable books find their places into our libraries, if readers were not prone to short circuits of this kind? The long list of things which refuse themselves to my reading capabilities, aren’t always written on a page. For example, my cats’ monologues are longue and they remain suspended in the air like a trail of smoke above her little white head waiting to be answered. I also lack the power to understand the needs of plants, and what yesterday looked green and healthy, today looks upset and faded. Maybe plants think we are dumb when we don’t understand them and our dumbness disappoints and poisons them.

PUNCTUATION SIGNS

Writing is weird and tiresome and I imagine Moses quite pissed off with this voice coming from the skies, verbose and patronizing giving him spoiler after spoiler. In all honesty, if Moses had some self-respect he would have raised his eyes towards the clouds and screamed „YHWE, my hand is numb.” I doubt the voice cared for punctuation signs. All exclamations and interogations we see in the sacred texts, all finished sentences, seem to stem from interior monologue in which the voice indulges.

When I started writing, the punctuation marks seemed an unimportant detail I could do without. One day, my teacher asked me to step in front of the classroom and read my text exactly as I wrote it. In those moments I felt this absence, a sort of white space that today would pass for an art manifesto. Between my sentences there was something missing, a special glue supposed not to put them together but keep them apart so they don’t spill into one another.

That’s how I realized there’s something in words, a children’s play. You can’t keep children in a place, they mix and run in all directions as if they were tireless particles.

But one of my greatest sin came later, when knowing how to use punctuation marks was no longer a joke but the proof that you are a good student. In my first year of university, when all figures were broad-shouldered and only gained their true size at the end, I heard the literature teacher accusing me that I put a comma between a subject and a predicate. What could I have answered her? „That’s where the voice in my head caught her breath?”. No. I apologized. Even so! For all of you purists, in 1785, Joseph Robertson accepts the unacceptable in his work, An essay on punctuation, and yells encore! encore! to the subject-comma-predicate.

It would be really interesting for someone to take punctuation marks seriously, to invent a police station, a hospital where commas can go and tell the truth about centuries of suffering at the hands of villains.

It’s really not that hard to imagine that punctuation marks didn’t always have the aspect we grew familiar with.

Across the centuries, they had plenty of time to grow a face and a tail to suit all tastes. There used to be a time when the point was a line and the comma was a chump, and the interrogation point was a doodle in the shape of a broken nose.

Their freedom of expression has drastically diminished with the invention of the printing machine some five hundred years ago and now they’re as boring as a room filled with politicians. You should invent you own punctuation marks, to think seriously of new shapes, minuscule or gigantic able to express both the muddiness of inexpressible states, the spit flying middair and the je ne sais quoi you feel in your chest when you think how productive you are going to be tomorrow.

Since I am here, I will try it myself. A sign I can call mine but insidious enough to pass unnoticed into the writings of others.

This is how Commaetta was born, the comma of revenge.

Commaetta is the duel. At the same time, in a poppy field it’s powerless. The signs preceeding the short tempered but patient Commaetta have to be perfect and the turn of the phrase awake, for hers is that whip the reader must search actively. The only acceptable reaction once the contact has been made is “ah!”. This is a vey refined sign which can not be obtained by the primitive gesture of pressing the keyboard. We must travel back in time when our fingers were blue and a trace of writing was always to be found on our body. Do you remember when the nib slipped raucously on the page cutting three rows from a single blow? That was a potential Commaetta, unintentional.

The true Commaetta is born out of revenge. You put it after a word you’d write in capitals, surrounded by flames, swarming with snakes, but since you are a calophile you write it inclined and add a Commaetta, meaning a comma with a nerve the sting of which a good reader will not miss.

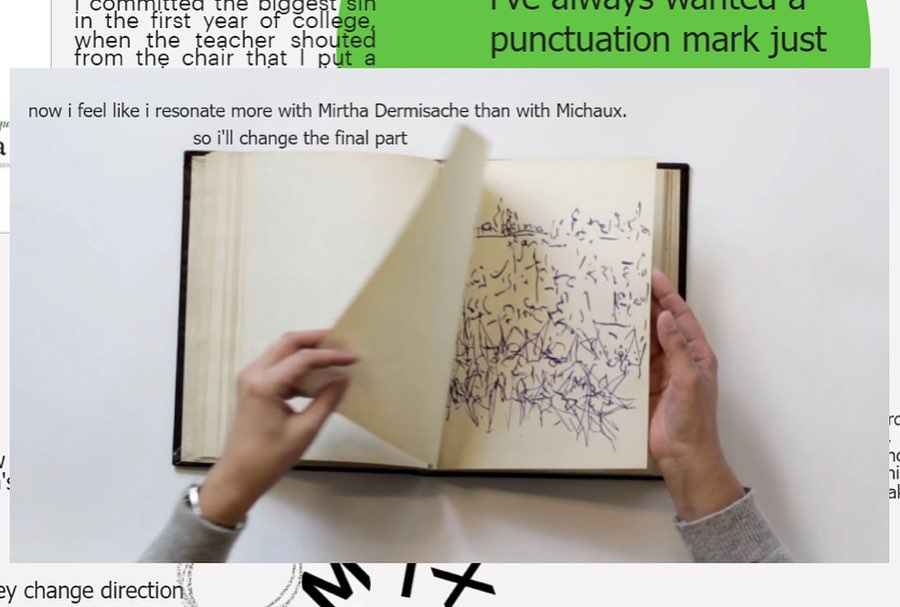

I thought about two artists well known into the realms of asemic writing: Henri Michaux and Mirtha Dermisache.

In the XIX century, the avanguards turned their focus to the straitjacket that letters have been made to wear. Beside Henri Michaux, the case of André Bazin is equally interested for he has invented some marks still in search of advocates. Michaux was born in a day of May, tired, as he himself said it : „Les nés-fatigués me comprendront. ” He came from a family of hat-makers living on a street called “DEFACQZ”. To sense on a daily basis the profound dissonance created by the conjunction “cqz” is not an easy thing and it can turn into peripatetics even the most surrealists among us. We don’t know if his experiences with graphical signs and writing find their origins in this childhood marked by hats, in the meeting with the graphite in pencils or in the name of that street. All we know is that Michaux wrote a lot, he was a graphician and a plastician, he travelled to India and dreamt about a universal language that he abandoned in favour of a dancing one ready to leave the paper.

Insects forced to live orderly in a blindingly white cell, letters are subject to the torture of calligraphy, this martial art of writing. The maxim guiding every learner, “writing beautifully”, which translates to respecting the letters’ curviness, is pure drudgery. When I was learning to write, my head was filled with beauty contests in which sharpness was like a wart on the nose, and a sentence beginning with an “M” or an “A”, made me cringe. The preceptor, role played by mum, didn’t agree with my ideas of curviness, proportion, dimension, so more than just a few times the pages of my notebook were flying across the room, bringing me again to the start line.

Fleas, leeches, the letters I was drawing were parasites eating away the paper and filling my mother with disgust. Twenty years later and I still have this weird feeling, that sharp letters are somehow imperfect.

Henri Michaux opposes to this typographical gaze and introduces through his jumpy, waltzing characters something we could call the multiple personality of the graphical sign, affection which frees writing from its figurative starvation to which the system doomed it. Mirtha Dermisache, on the other hand, refused to make from her asemic writings separate works of art to be hung on the walls of a gallery. Instead, she collected them into books which she wanted to be read as any other book. But imagine telling you children asemic stories before bed. Imagine having to read a bibliography of asemic poems for your incoming exam. My answers would certainly be asemic too. Praised by Roland Barthes in a letter dating from 25 mars 1971 for bringing to the surface the ritualistic essence of writing, Dermisache’s texts are, despite everything, highly readable. What makes them so? I would answer that reading is so ingrained into our minds that we can not look at a line without a slight desire to know where and how it ends and what does it mean. In our digitalized age, when handwriting disappears and there’s no trace of ink on our hands, we seem to treat everything surgically. A blank page is no longer full of parasites, the fear of error gives our garden a stern impoverished air.

Alexandra Samoilă lives in Lyon.